One of the finest and most influential structural geologists of modern times

John was born and raised in north London. He excelled in mathematics and chemistry, and developed great abilities in running, cycling, rock climbing and mountaineering, as well as a great interest in music, learning to play the cello. John came to love the natural world. He won a State Scholarship and was accepted by Imperial College London to read geology.

Mapping

John’s undergraduate mapping of the Tryfan Syncine is a masterpiece and was a harbinger of the field skills for which he would become famous. John graduated with First Class Honours, then completed his Ph.D., in two years, on the Loch Monar district, producing his second brilliant map. In Monar, John showed how sections through polyphase folds can generate very complicated patterns, and how outcrop structures may be used to determine the large-scale structures.

A short post-doctoral period was followed by two years of military service. John then returned to Imperial College London as a Lecturer and developed a Masters course in structural geology, attended by many who were to become distinguished researchers, such as Mike Coward. During a sabbatical leave at the University of the Witwatersrand, John made superb detailed maps of the metasediments of the central Barberton Mountain Land and of the Chinamora Batholith and its margins.

John later moved to a Chair in Leeds in 1973, when he continued mapping the whole Glenelg region, showing the enormous extent of the pre-Moine basement and its unconformity. In 1977, John moved to a Chair at the ETH in Zurich, Switzerland where he and his wife Dorothee mapped in the Helvetic Alps, and demonstrated that most of the nappes are cylindroidal.

John’s six-inch field sheets were masterworks of the finest detail and clarity, comparable with those of C. T. Clough in the Scottish Highlands during the late 1800s. His maps and field photographs were beautiful works of art; he also painted in oils superbly. He combined this with a powerful three-dimensional ability, and a thorough mathematical and engineering approach.

John published “Folding and Fracturing of Rocks” in 1967, and more recently, with co-authors Richard Lisle and Martin Huber, “The techniques of Modern Structural Geology”. From microscope to outcrop and region, John was able to convey much of his love and understanding of rocks to his students and colleagues.

Retirement

In retirement in the idyllic Ardeche, France, John grew olives, fruit and vegetables, composed music and poetry, and ran music schools. He continued with geology, albeit at a lesser pace, with conferences, field trips, and mapping in Glenelg.

John was a quiet, modest, undemonstrative, and thoughtful man, with an intense love of beauty in everything from rocks to music, painting, and landscapes. He was kind and ready to help anyone, always had time to discuss and explain the finer points of a structural problem, sought the opinion of others, avoided confrontation, and was non-judgemental.

John was showered with many honours, medals including the Wollaston Medal, and honorary degrees. He was appointed CBE, and elected to national academies including the Royal Society of London and the US National Academy of Sciences. His sixtieth birthday was celebrated by a conference in Zurich and an Alpine field trip. His eightieth birthday involved a smaller Alpine field trip.

John will be remembered as a great scientist, internationalist, and human being.

By John Dewey

The full version of this obituary appears below. Editor.

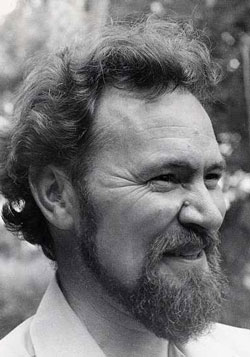

John Ramsay (17th June 1931 – 12th January 2021)

With the death of John Ramsay, peacefully in his sleep just before his 90th birthday, science has lost the finest and most influential structural geologist of modern times. John was born and raised in Edmonton, north London where, at secondary school, he excelled in mathematics and chemistry, developed great abilities in running cross-country and the half-mile, and became an avid cyclist, Scout, rock climber, and mountaineer.

As a teenager, he developed a great interest in music, learning to play the cello. Especially, he came to love the natural world and the ‘great outdoors’. He won a State Scholarship and was accepted by Imperial College London to read geology.

John’s undergraduate mapping of the Tryfan Syncine is a masterpiece and was a harbinger of the field skills for which he would become famous. John became an excellent cellist and honed his climbing skills in North Wales and the Lake District. He graduated with First Class Honours, then completed his Ph.D., in two years, on the Loch Monar district, producing his second brilliant map. In Monar, John recorded great numbers of observations that showed how sections through polyphase folds can generate very complicated patterns, and how outcrop structures may be used to determine the large-scale structures.

A short post-doctoral period was followed by two years of military service, as a cellist and tenor drummer in the band of the Army Corps of Engineers. John then returned to Imperial College London as a Lecturer and developed a Masters course in structural geology, attended by many who were to become distinguished researchers, such as Mike Coward. During a sabbatical leave at the University of the Witwatersrand, John made superb detailed maps of the metasediments of the central Barberton Mountain Land and of the Chinamora Batholith and its margins.

John later moved to a Chair in Leeds in 1973, when he continued mapping the whole Glenelg region, showing the enormous extent of the pre-Moine basement and its unconformity beneath the Moine. In 1977, John moved to a Chair at the ETH in Zurich. Until his early retirement in 1992, he and his wife Dorothee did a huge amount of mapping in the Helvetic Alps, and demonstrated that most of the nappes are cylindroidal.

John’s six-inch field sheets were masterworks of the finest detail and clarity, comparable with those of C. T. Clough in the Scottish Highlands during the late 1800s. His maps and field photographs were beautiful works of art; he also painted in oils superbly. He combined this with a powerful three-dimensional ability, and a thorough mathematical and engineering approach.

John published the first thoroughly modern book on structural geology, “Folding and Fracturing of Rocks” in 1967, and more recently, with co-authors Richard Lisle and Martin Huber, the comprehensive three-volume work “The techniques of Modern Structural Geology”. From microscope to outcrop and region, John was able to convey much of his love and understanding of rocks to his students and colleagues in the field, as well as in lectures and conversations.

In retirement at sixty to the idyllic French village of Issirac in the Ardeche, John grew olives and a wide variety of fruit and vegetables, arranged and composed music including four very well received and reviewed string quartets, ran music schools, and composed poetry. He continued with geology, albeit at a lesser pace, with conferences, field trips, and mapping in Glenelg.

John was a quiet, modest, undemonstrative, and thoughtful man, with an intense love of beauty in everything from rocks to music, painting, and landscapes. He was kind and ready to help anyone, always had time to discuss and explain the finer points of a structural problem, always sought the opinion of others, avoided confrontation, and was non-judgemental. John thought that team sports cause a lot of ill-will, but was a very fine downhill skier. He was showered with many honours, medals including the Wollaston Medal, and honorary degrees. He was appointed CBE, and elected to national academies including the Royal Society of London and the US National Academy of Sciences. His sixtieth birthday was celebrated by a conference in Zurich and an Alpine field trip. His eightieth birthday involved a smaller Alpine field trip; both were physically and intellectually testing. John will be remembered as a great scientist, internationalist, and human being.

By John Dewey